“People tend to approximate the product rather than attacking it in a realistic, true way at any elementary level — regardless of how elementary — but it must be entirely true and entirely real and entirely accurate. They would rather approximate the entire problem than to take a small part of it and be real and true about it. To approximate the whole thing in a vague way gives you a feeling that you’ve more or less touched the thing, but in this way you just lead yourself toward confusion and ultimately you’re going to get so confused that you’ll never find your way out.”

—Bill Evans

My weekend-morning routine starts with brewing a cup of coffee, then cycle through the open tabs I bookmarked for my future self and close the loop.

I was listening today to Linear’s Conversations on Quality. Insightful, thoughtful—the angle people like me usually miss. I kept Stripe’s Jeff Weinstein interview on repeat while I wrote this. He fires off claim after claim; I’d felt the itch behind several, yet in hindsight I’m still not sure I truly understand them.

The interview’s core idea is that a great product isn’t the sum of meticulously polished features; it’s that one feature that tackles a problem so urgent customers would “cancel the rest of their day” to get it fixed. The deadliest mistake is to perfect the wrong thing from the start.

Some of the points below are well-worn, almost obvious, but the checklist is for me; some of my writing is just a trail of reminders. Wisdom, after all, is keeping timeless truths from slipping through your fingers.

Is your problem big enough to halt someone’s day? Don’t focus on minor pet peeves or “wouldn’t it be cool if” ideas. Is it a top-tier problem? Customers will pay to solve their #1 or #2 problems, but not problem #38. Are you polishing the wrong product? No matter how much you polish a solution for a problem that isn’t big enough, it won’t go anywhere. The core problem must be significant before you focus on beautifying the solution. However, beautifying the solution matters.

Did you get out of your own head? The best way to understand the customer’s reality is to talk to them—and then simply listen. Don’t pitch. The most valuable information usually surfaces at the end of the conversation, once guards are down. As with intimate relationships, offer space. I used to struggle with this outside of obviously intimate contexts, but seen critically, every successful relationship is an intimate one.

Did you focus on the core functionality first? Before beautifying every part of an application, ensure the core functions (the rule of three) are fast, reliable, and easy to use. Are you building iteratively with your users? Instead of spending months on a big launch, open a Google Doc with a customer and co-design the solution. The tight feedback loop guarantees you’re building what they actually need. Do you aim for “surprisingly great,” not just “quality?” The goal is to solve the problem so well that the experience feels delightful. That comes from anything that removes friction.

Would users scream if your product went down? Weinstein tells of a product that went offline without a single customer complaint. This was a quiet proof it was never solving a critical problem. If your service is essential, the outage will scream. Do you feel constantly behind? If you’re solving a burning problem, customers will haul you forward with a steady stream of requests and a heat you can feel. That perpetual sense of “always behind” is usually the surest sign you’ve struck something worth fixing. I wake up with it in my gut most days. Nothing stings like second place, and life keeps finding new ways to teach that lesson.

Do you maintain a healthy ego? You have to believe you’re capable of building something truly groundbreaking—yet that ego must be tempered by self-awareness and aimed at propelling the team, not just feeding your own ambition. Are you guided by ownership and decisiveness? The one lesson I’ve (positively) internalized from Amazon is this: ownership is the quietest, most powerful corporate virtue. It’s brutally simple—the problem is yours, so you fix it. Layer decisiveness on top and you get the rock-star leather-jacket rush that turns ownership into urgency; suddenly you’re volunteering for riskier problems and chasing solutions big enough to scare you.

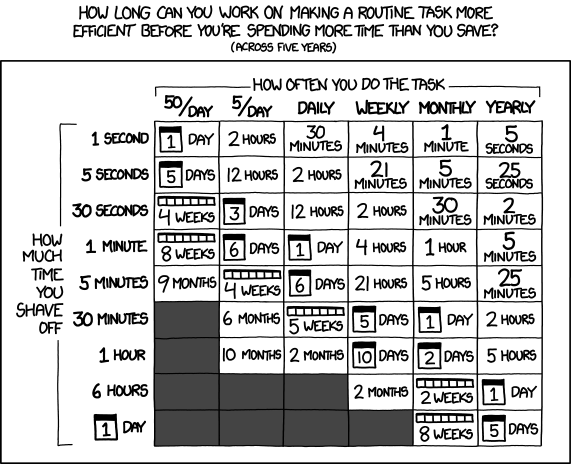

Circling back to the xkcd “Is It Worth Your Time?” strip: pick a task that actually pays back the minutes you invest in automating it. I like this bias—it’s a quick workout for the mind.

Now, casting the line: if your prospect runs a task F times a year and you automate away T hours each time, you give back F × T × 5 years over the next half-decade. Multiply those hours by the customer’s internal cost per hour and you’ve sized the value pool.

If a tool erases a painful workflow, my ceiling is (maybe) 10–30% of the value pool. Crank up the frequency (F) or the time saved per run (T) and the cap rises, but if you let that F × T shrink, the deal evaporates.

It feels obvious now.